Late-Term Abortions

As a brief interlude from my series on abortion and legislation, I want to take the time to talk about late-term abortions and the reasons why they occur. In multiple online discussions, I’ve encountered individuals who are firmly convinced that late-term abortions only occur for medical reasons, i.e. the health of the mother or the foetus. I strongly suspect that this may be the result of the film ‘After Tiller’, which attempts to portray the four remaining late-term abortionists in America as sympathetically as possible. There are also those who insist that late-term abortions are in fact early inductions where the life of the foetus is preserved if at all possible. This post will be a sharing of the various resources, articles and interviews that I’ve come across that clearly show that neither of these are the case. Late-term abortions are intended to end the life of the unborn child and are carried for any number of reasons that have nothing to do with health/medical indications. I will add to the list as I get opportunity.

NB: the definition of ‘late-term’ varies, but most sources seem to place abortions after 16-20 weeks gestation in the late-term category.

1. An interview with late-term abortionist Dr Susan Robinson, in which she describes how she will abort healthy foetuses late in pregnancy, and also how a lethal injection is given to the foetus as part of the procedure to ensure death.

2. Another interview with Dr Robinson, where it’s very clear that many of the women who see her are coming for a late-term abortion because they didn’t know they were pregnant or because their circumstances changed (be prepared for some appalling stereotyping of the pro-life movement, if you choose to read through the entire interview).

3. A report on the ‘After Tiller’ documentary (unfortunately, this article no longer seems to be on the site) and the abortionists involved, the relevant quote is a bit buried, so I’ve reproduced it here:

“The hands of Susan Robinson covering her face as she ponders another young woman’s story and whether as a physician of late-term abortions, she says yes or no.

“Who am I to say, ‘No, that’s not a good enough story’? What if you’re just not a good storyteller? The point is,” Robinson says, “she has made this decision. If I’m going to turn down a patient, it’s because it’s not safe and I can’t take care of her.“” (emphasis mine).

4. A combined 5.1% of abortions in the U.S.A are performed at 16+ weeks; that’s 3.8% between 16 and 20 weeks, and 1.3% at 21+ weeks. That’s approximately 35,000 and 12,000 abortions in 2013 respectively.

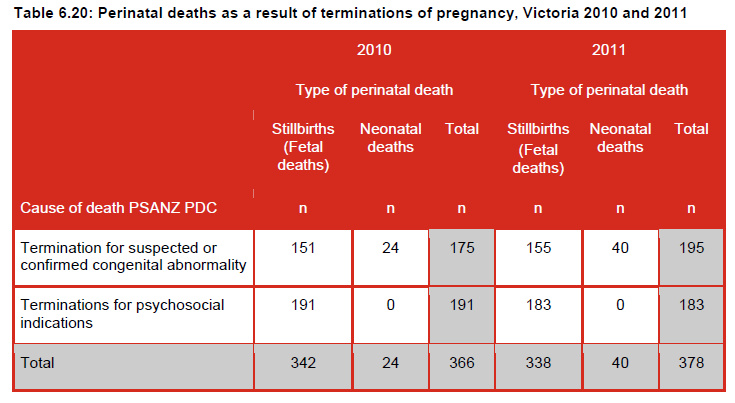

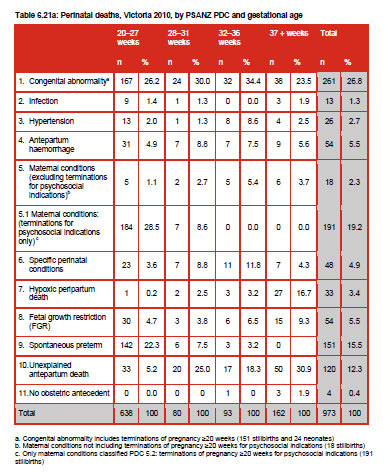

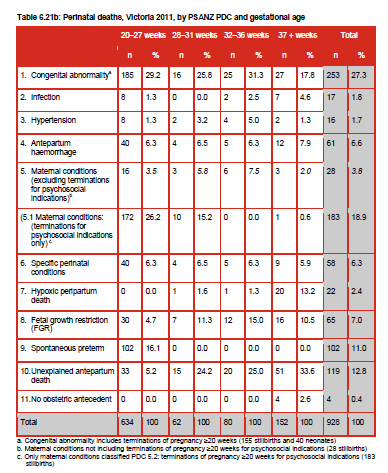

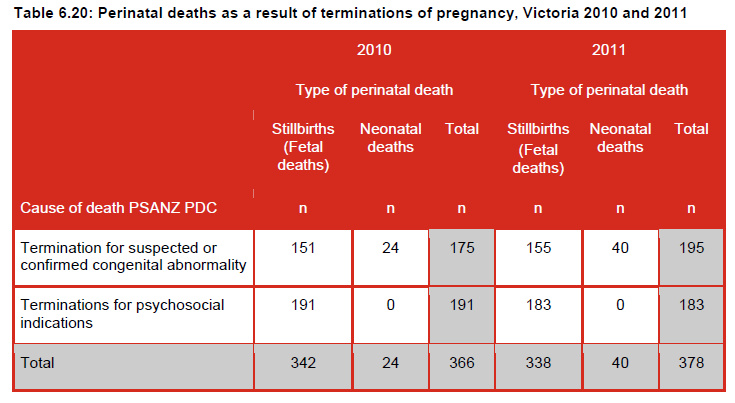

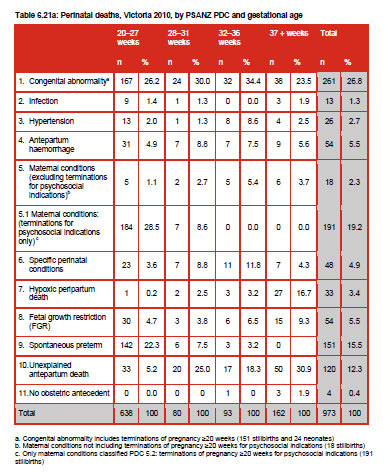

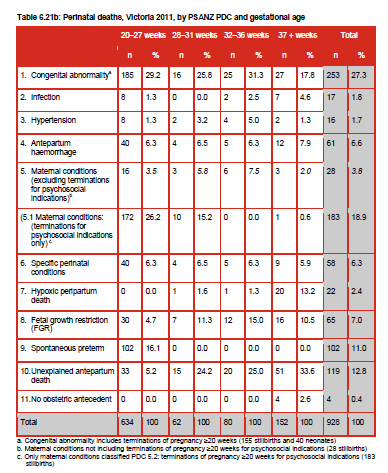

5. In Victoria, Australia, perinatal deaths at 20+ weeks gestation are recorded in mortality reports (I’ve included page numbers, as this is a lengthy document, and also reproduced the relevant tables).

In 2010:

• 191 foetuses were aborted because of maternal psychosocial conditions (i.e. reasons of mental health or social circumstances). None survived to birth (p159).

• 184 were aborted between 20 and 27 weeks gestation (p164).

• 7 were aborted between 28 and 31 weeks gestation (p164).

• In the same time period, 28 foetuses were aborted at 20+ for maternal conditions, including 6 at 32 to 36 weeks and 3 at 37+ weeks (p164). None survived to birth (p162).

In 2011:

• 183 foetuses were aborted because of maternal psychosocial conditions, again with none surviving to birth (p159).

• 172 of these abortions occurred between 20 and 27 weeks gestation (p162).

• 10 occurred between 28 and 31 weeks gestation (p162).

• 1 occurred at 37+ weeks gestation (full-term) (p162).

• In the same time period, 18 foetuses were aborted for maternal conditions, including 5 at 32 to 36 weeks and 6 at 37+ weeks (p162). None survived to birth (p160).

As you can see, this data gives lie to the idea that late-term abortion is only for health conditions, and that the aim of a late-term abortion is to deliver a live baby whenever possible.

6. Although this article refers specifically to partial-birth abortions (or intact dilation and extraction method), it quotes several abortionists on the reasons why women have late-term abortions.

7. An article on reasons why women present for second trimester (14 to 26 weeks) abortions, citing the main reasons as logistical, not suspecting pregnancy and difficulty in making the decision to abort.

8. Abby Johnson, former clinic director at Planned Parenthood and now pro-life advocate states that the women sent for abortions at 24+ weeks did not have medical reasons for doing so.

9. Another interview with Dr Robinson. I’ve reproduced the relevant quote;

“It’s about these poor desperate women who find out they’re pregnant and they’re already three quarters of the way through pregnancy and a pregnancy will wreck their life. What are they supposed to do? Those are the people we take care of. We take care of people whom pregnancy would wreck their life or who have a baby that’s hugely damaged to the point where the parents who wanted this pregnancy think that perpetrating a life on this kid is unfair.”

10. An undercover video of a young woman at 26 weeks pregnant seeing Dr LeRoy Carhart for an abortion. The relevant moment is at 4:25. It also clearly shows that there is no intention for the foetus to be born alive.

11. An interview with late-term abortionist Willie Parker. He’s never explicit, but reading between the lines it’s fairly clear that he carried out late-term abortions for non-medical reasons:

12. An article about a Los Angeles clinic performing abortions up to 26 weeks. A couple of the relevant quotes;

“It is a private clinic, run by a former general practitioner, that does about 150 abortions a week. It accepts patients 26 weeks into their pregnancies. Asked the obvious question, the administrator sighs and says, “We have kind of gotten out of the habit of asking why they waited so long.””

“The realities that Walshe sees every day, she admits, can be unsettling. “These women know they are pregnant, but not until the 16th or 17th week, when the fetus is kicking and bothering them, do they say, ‘Oh, I have to deal with this,’ ” she says. “It’s not that these women are bad, or they’re wrong. They’re just poor. They don’t lead organized, routine lives.””

13. The Clinic Quotes websites shares a multitude of quotes on abortion from many and varied sources. This page is specific to quotes on late-term abortions.

14. An article on why women seek abortions at 20+ weeks. Medical reasons are only brought up in describing the demographic of the sample; 30% had a substance abuse or mental health issue – although this was associated by the author with delay rather than reasons for abortion.

• “ 43% of women reported that not realizing they were pregnant delayed them in seeking abortion care.”

• “37% of women reported that the process of deciding whether to have an abortion slowed them down.”

• “One in five participants said that disagreement with the man involved in the pregnancy over their decision to have an abortion slowed them down.”

• “Some women had trouble finding a place to go … 38% of these women reported delay for this reason.”

• “Almost two-thirds of the women seeking later abortion … said they were delayed because they were raising money for travel, the procedure and other costs.”

• “Women seeking later abortions were twice as likely as women seeking first-trimester abortions to report delays because of difficulties securing public or private insurance coverage for the abortion.”

(Full-text here if you have access)

15. An article from Pro-Life Obs/Gyns on late-term abortion and medical necessity.

16. An article on Ron Fitzsimmons (then executive director of the National Coalition of Abortion Providers) comments about having lied regarding medical necessity and late-term abortions.

17. A Slate article in the aftermath of the Kermit Gosnell charges talks about elective late-term abortion, amongst other things.

18. An article by late-term abortionist, Lisa Harris. In case you cannot access the full-text, I’ve reproduced the relevant quote below;

“In the US, the known risk factors associated with presenting for second trimester abortion include: adolescence, drug and alcohol addiction, poverty, difficulty obtaining funding for the abortion, and African-American race. Delays in obtaining second trimester abortion come when a woman does not realise she is pregnant (perhaps a surrogate for poor health or lack of education), has logistical delays, experiences denial about the pregnancy, is uncertain about the decision to have an abortion, or has a change in life circumstances or relationships that makes a previously desired pregnancy undesired.”

And because it really stood out to me, here is another comment she made on the difference between the 23-week old foetus she had just aborted, and the 23-week old premature infant who she observed being treated in the neonatal unit. Note how she considers only extrinsic factors in deciding the legitimacy of dismembering one child while striving to save the other;

“Yes, I understand that the vital difference between the fetus I aborted that day in clinic, and the one in the NICU was, crucially, its location inside or outside of the woman’s body, and most importantly, her hopes and wishes for that fetus/baby.”

19. An Australian couple abort their 28-week unborn child in due to a condition called ectrodactyly, which had only been discovered to affect the left hand and is not a lethal condition. From the father:

“”It felt very inhumane, to be honest,” Frank said. “We were being told that our only option was to give birth to a baby that we did not wish to give birth to at all.We felt we have been forgotten and abandoned through the political and judicial uncertainty of the abortion laws”.”

20. Another Australian couple aborted their 32-week unborn child in 2000, due to suspected dwarfism, another non-lethal condition. The mother was reported to be suicidal and the abortion carried out for this reason, but it highlights the fact that this late-term abortion was intended to kill the unborn child. There was absolutely no intention that the child should live, even though its chance of survival would have been extremely high. The prenatal diagnosis of dwarfism was never confirmed.

21. A study by Maria Stopes International UK, “Late Abortion: A Research Study of Women Undergoing Abortion Between 19 and 24 Weeks Gestation” found that:

“For the vast majority of women taking part in this study, the signs and symptoms of pregnancy were not recognised until an advanced stage, making late abortion an inevitability rather than a conscious choice on their part.”

and

“A small minority of women taking part were aware of the pregnancy at an early stage but were either in denial, or subsequently faced a significant change in their circumstances that forced them to re-evaluate their pregnancy.”

22. Descriptions of second and third trimester abortions from Warren Hern’s website. A three to four day procedure is hardly what is necessary for a woman whose life is endangered by her pregnancy.